All Exhibitions here

With Paris set to host the Olympic and Paralympic Games for the first time in a hundred years, from 4 April to 1 September 2024 the Musée Marmottan Monet is presenting an exhibition devoted to the representation of sport from 1870 to 1930, featuring around a hundred works from international private and public collections, including a sculpture by Aristide Maillol.April 27, 2024

View of the exhibition ‘En jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930)’ at the Musée Marmottan Monet © Studio Christian Baraja SLB

View of the exhibition ‘En jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930)’ at the Musée Marmottan Monet © Studio Christian Baraja SLB Navigating from Impressionism to Cubism, the exhibition ‘En jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930)’ explores how sport, its practitioners and its events are represented as emblematic subjects of modernity and avant-garde movements. While Pierre de Courbertin reinvented the Olympic Games by modernising them, the world of sport underwent a series of transformations that were closely observed by artists. Initially seen as a pastime associated with the English aristocracy in the nineteenth century, sport gradually gained in popularity on the European continent and in the United States, becoming a mass leisure activity at the beginning of the following century, oscillating between spectacle and practice. The exhibition examines the ethical implications and aesthetic expressions of sporting representations, not only through the works of Monet, Degas, Caillebotte, Toulouse-Lautrec, Eakins, Richier and Rodin, but also through the more modern works of Bellows, Lhote, Delaunay, Metzinger and Gromaire. It questions the metaphorical significance of the figure of the artist as sportsman. But it also embodies determination, endurance and a form of resistance through the convergence of elite practices such as horse-riding and sailing, and more archaic, working-class disciplines such as wrestling, boxing and cycling.

Aristide Maillol, « Le cycliste », 1907, Bronze, 98 x 30 x 24 cm

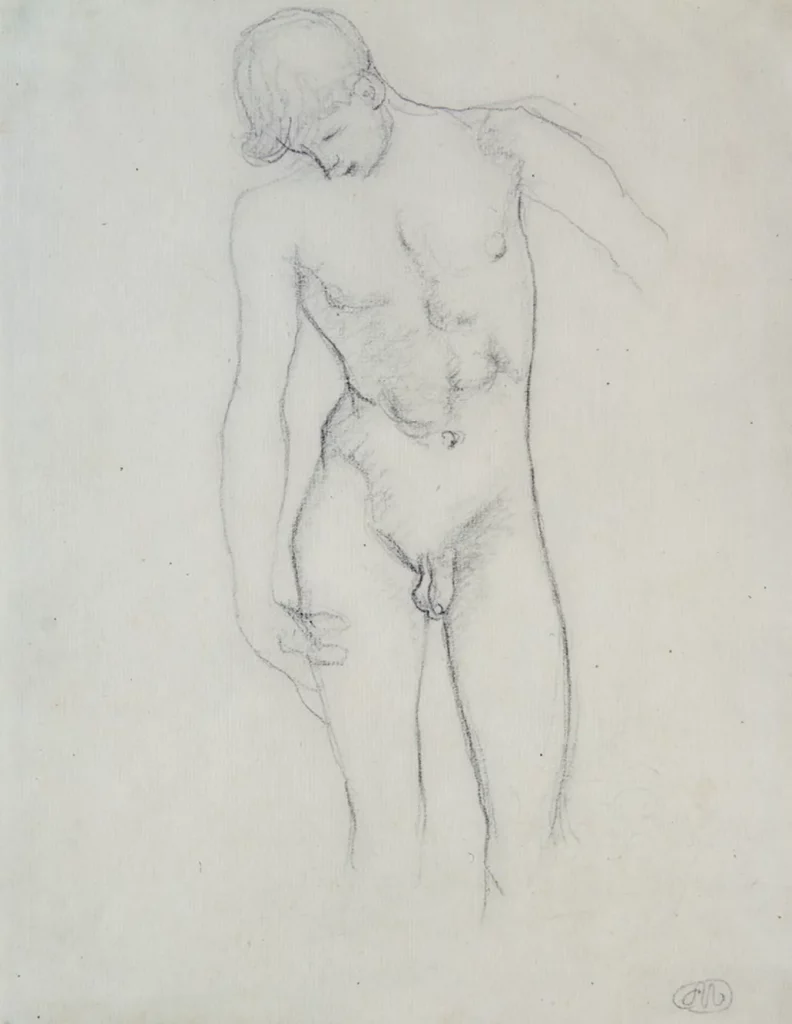

Aristide Maillol, ‘Gaston Colin de face, étude pour Le Cycliste’, 1907, Graphite on watermarked paper, H. 30.2 ; W. 23.5 cm, Paris, Fondation Dina Vierny - musée Maillol

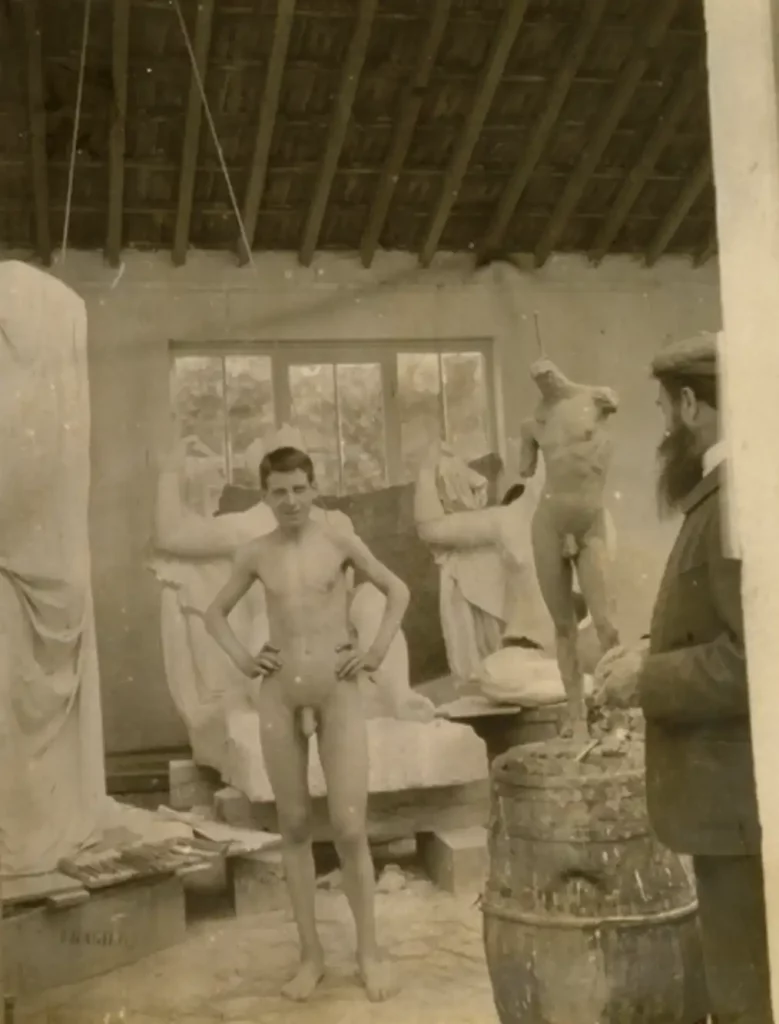

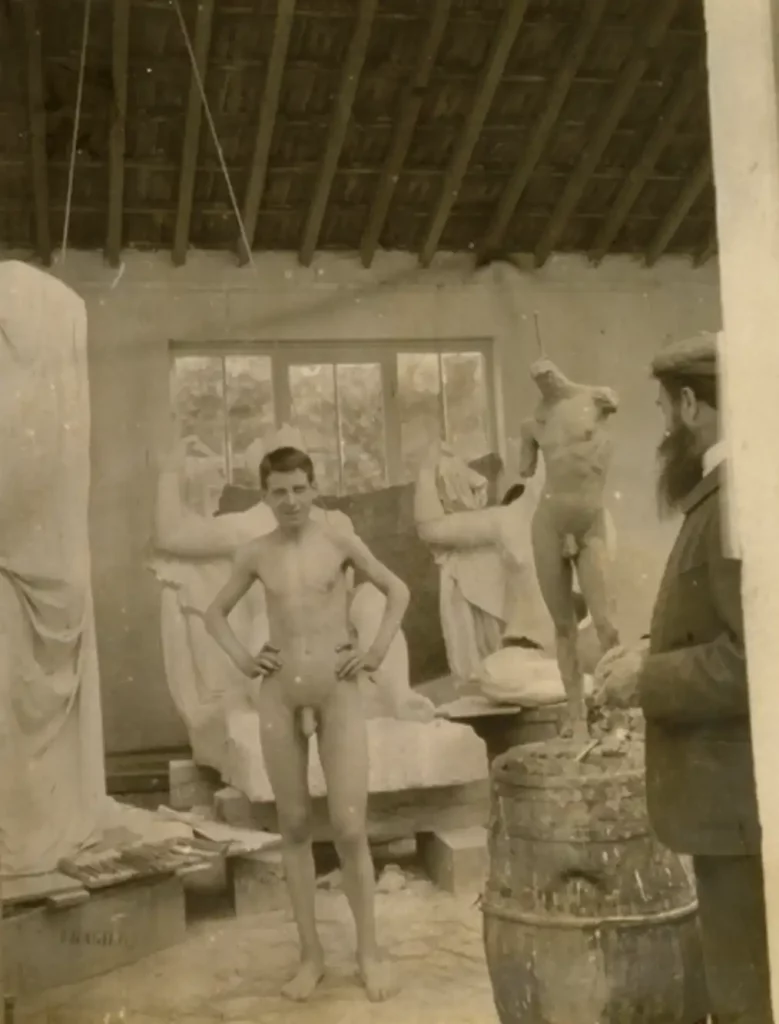

To mark the occasion, the Dina Vierny Gallery has facilitated the loan of a major work by Aristide Maillol produced in 1907: ‘The Cyclist’. It was commissioned by Count Harry Kessler, Maillol's first major patron, who wanted to have a ‘Narcissus’ sculpted and at the same time own a sculpture representing his partner, the cyclist Gaston Colin. This is one of the very few male representations by Maillol, of which there are three: an ‘Athlete’, a ‘Dying Warrior’ and this ‘Cyclist’, whose slender body and fine musculature correspond to Gaston Colin's sporting activities. The work was so naturalistic that the sculptor Medardo Rosso insinuated that it had been cast from life. This almost exact transposition of the model was a source of concern for the artist: ‘It's too natural, there's no denying it, it's too natural! [...] Because of that, [it] will always have a rather special position in my work. Maillol suggested to Count Kessler that he inscribe the young man's name on the plinth, in order to revive the great tradition of the portrait of an athlete: ‘The ancients did paint portraits of athletes. Well, this is an athlete's portrait. I was perhaps the first person to redo a statue of an athlete. For Gaston Colin, it was a consecration. This sculpted portrait gave him a heroic dimension and access to immortality, for he was the son of a showman who had nothing to do with becoming a kind of modern hero. In his diary, Harry Kessler documented the various stages in Maillol's creative process. He describes his visits to the artist's studio, the modelling of the wax, etc. He also illustrates his account with precious photographs taken in the studio in 1907, showing Gaston Colin posing for the sculptor. These exceptional documents allow us to discover for the first time, and in an extremely precise and dated manner, Maillol's creative process.

Aristide Maillol et Gaston Colin avec 'Le Cycliste' © Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, Estate of Harry Graf Kessler

Gaston Colin and Aristide Maillol with 'The Cyclist' in Maillol's studio at Marly-le-Roi © Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, Nachlass Harry Graf Kessler

To mark the occasion, the Dina Vierny Gallery has facilitated the loan of a major work by Aristide Maillol produced in 1907: ‘The Cyclist’. It was commissioned by Count Harry Kessler, Maillol's first major patron, who wanted to have a ‘Narcissus’ sculpted and at the same time own a sculpture representing his partner, the cyclist Gaston Colin. This is one of the very few male representations by Maillol, of which there are three: an ‘Athlete’, a ‘Dying Warrior’ and this ‘Cyclist’, whose slender body and fine musculature correspond to Gaston Colin's sporting activities. The work was so naturalistic that the sculptor Medardo Rosso insinuated that it had been cast from life. This almost exact transposition of the model was a source of concern for the artist: ‘It's too natural, there's no denying it, it's too natural! [...] Because of that, [it] will always have a rather special position in my work. Maillol suggested to Count Kessler that he inscribe the young man's name on the plinth, in order to revive the great tradition of the portrait of an athlete: ‘The ancients did paint portraits of athletes. Well, this is an athlete's portrait. I was perhaps the first person to redo a statue of an athlete. For Gaston Colin, it was a consecration. This sculpted portrait gave him a heroic dimension and access to immortality, for he was the son of a showman who had nothing to do with becoming a kind of modern hero. In his diary, Harry Kessler documented the various stages in Maillol's creative process. He describes his visits to the artist's studio, the modelling of the wax, etc. He also illustrates his account with precious photographs taken in the studio in 1907, showing Gaston Colin posing for the sculptor. These exceptional documents allow us to discover for the first time, and in an extremely precise and dated manner, Maillol's creative process.

View of the exhibition ‘En jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930)’ at the Musée Marmottan Monet © Studio Christian Baraja SLB

View of the exhibition ‘En jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930)’ at the Musée Marmottan Monet © Studio Christian Baraja SLB With Paris set to host the Olympic and Paralympic Games for the first time in a hundred years, from 4 April to 1 September 2024 the Musée Marmottan Monet is presenting an exhibition devoted to the representation of sport from 1870 to 1930, featuring around a hundred works from international private and public collections, including a sculpture by Aristide Maillol.

Navigating from Impressionism to Cubism, the exhibition ‘En jeu! Artists and Sport (1870-1930)’ explores how sport, its practitioners and its events are represented as emblematic subjects of modernity and avant-garde movements. While Pierre de Courbertin reinvented the Olympic Games by modernising them, the world of sport underwent a series of transformations that were closely observed by artists. Initially seen as a pastime associated with the English aristocracy in the nineteenth century, sport gradually gained in popularity on the European continent and in the United States, becoming a mass leisure activity at the beginning of the following century, oscillating between spectacle and practice. The exhibition examines the ethical implications and aesthetic expressions of sporting representations, not only through the works of Monet, Degas, Caillebotte, Toulouse-Lautrec, Eakins, Richier and Rodin, but also through the more modern works of Bellows, Lhote, Delaunay, Metzinger and Gromaire. It questions the metaphorical significance of the figure of the artist as sportsman. But it also embodies determination, endurance and a form of resistance through the convergence of elite practices such as horse-riding and sailing, and more archaic, working-class disciplines such as wrestling, boxing and cycling.

To mark the occasion, the Dina Vierny Gallery has facilitated the loan of a major work by Aristide Maillol produced in 1907: ‘The Cyclist’. It was commissioned by Count Harry Kessler, Maillol's first major patron, who wanted to have a ‘Narcissus’ sculpted and at the same time own a sculpture representing his partner, the cyclist Gaston Colin. This is one of the very few male representations by Maillol, of which there are three: an ‘Athlete’, a ‘Dying Warrior’ and this ‘Cyclist’, whose slender body and fine musculature correspond to Gaston Colin's sporting activities. The work was so naturalistic that the sculptor Medardo Rosso insinuated that it had been cast from life. This almost exact transposition of the model was a source of concern for the artist: ‘It's too natural, there's no denying it, it's too natural! [...] Because of that, [it] will always have a rather special position in my work. Maillol suggested to Count Kessler that he inscribe the young man's name on the plinth, in order to revive the great tradition of the portrait of an athlete: ‘The ancients did paint portraits of athletes. Well, this is an athlete's portrait. I was perhaps the first person to redo a statue of an athlete. For Gaston Colin, it was a consecration. This sculpted portrait gave him a heroic dimension and access to immortality, for he was the son of a showman who had nothing to do with becoming a kind of modern hero. In his diary, Harry Kessler documented the various stages in Maillol's creative process. He describes his visits to the artist's studio, the modelling of the wax, etc. He also illustrates his account with precious photographs taken in the studio in 1907, showing Gaston Colin posing for the sculptor. These exceptional documents allow us to discover for the first time, and in an extremely precise and dated manner, Maillol's creative process.

Aristide Maillol et Gaston Colin avec 'Le Cycliste' © Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, Estate of Harry Graf Kessler

Gaston Colin and Aristide Maillol with 'The Cyclist' in Maillol's studio at Marly-le-Roi © Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, Nachlass Harry Graf Kessler